The English-Language Cryptex That Is "Spelling Bee"

It's just a game, yes. But no, wait: is it, in fact, JUST a game?

Like many people, I like playing word games as a means of relaxing, exercising my mind, and — perhaps — fending off mental decrepitude later in life. Yes, I do Wordle, and also something called Waffle, and I’ve done crossword puzzles and acrostics for almost my entire adult life.

But my favorite, for the last year-plus, has been a simple game called Spelling Bee.

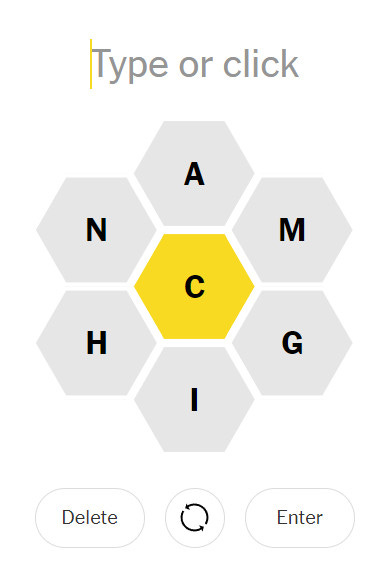

As you can see from that link, it’s one of the New York Times suite of games (which includes Wordle and the venerable crossword puzzle). The playing board, so to speak, looks like this (from the game for Saturday, December 2, 2023):

The premise: you’re given a selection of seven different letters, from which you have to assemble as many words as you can, under these constraints:

Each word must be four or more letters long. (Therefore, although CAN is a valid English-language word, it’s not a valid Spelling Bee word, and will be rejected.) There’s no maximum length, though.

A given word can include zero or more occurrences of any of the seven letters — in this case, there might be (say) no As at all — or there might be four or five As, zero or one or ten Cs, and so on.

The letter in the gold hexagon in the center must be used at least once for a word to be “valid” for the day. In this case, for instance, HANG is a valid word in general, but isn’t acceptable — today — because it doesn’t include a C.

The most problematic limit: even if it meets all the above constraints, a word can still be rejected for the following reasons (emphasis added): “Our word list does not include words that are obscure, hyphenated, or proper nouns… No cussing either, sorry.” This particular limitation drives me (and many others) crazy; what’s “obscure,” for instance, in a world where one person’s common knowledge is another’s impenetrable black box? Also, “our word list” includes some “valid” words which are no better than arguable… In one particularly egregious case, a couple weeks ago, ALRIGHT was just fine. “Our word list” also seems skewed towards more recent language history, so (say) DOXX has proved (ahem) alright, while SKIDOO, probably not. (To be fair, I haven’t actually had a chance to try out the latter.)

All the rules and reasons for complaining, though, aren’t what keep me playing Spelling Bee…

In Dan Brown’s popular thriller The Da Vinci Code, the protagonists must solve a mystery which at one point requires them to make use of a cryptex. This word didn’t exist before Brown invented it for his book (note to self: see if CRYPTEX is a valid Spelling Bee word, should those letters ever come up); there’s a photo of such a device at the top of this post. The idea is that you have a cylinder whose surface comprises a series of rings, each with letters of the alphabet embossed on it. The cryptex is actually a combination safe: when you’ve turned all the rings so their letters line up a certain way, the cylinder opens up to reveal a secret message.

Although it is not clear whether the alphabet in question preserves the U/V and/or I/J distinctions and/or includes the letter W, when only the alignment of the disks with respect to each other is considered, the number of potential combinations is between 234 (279,841) and 264 (456,976); if the mechanism treats combinations having the same disk alignment but different degrees of rotation around the cylinder's long axis as distinct, as does a multiple-wheel combination lock or slot machine employing an indicator bar along which the specified numbers are to be aligned, this number rises to between 235 (6,436,343) and 265 (11,881,376).

In other words, regardless of the details: a hell of a lot of combinations.

That’s Spelling Bee, in a nutshell. On a given day, each ring has only seven letters on it, and the actual number of rings ranges between four and infinity. Also, in other words, a hell of a lot of combinations.

Except for that one central-letter constraint. And except for the limited “our word list.”

But the goal is not insurmountable, because, well, not all possible combinations are worth even trying in the first place. Consider:

What are the odds that an English-language word will contain the letters HGC, in that order? Effectively, zero. For that matter, you can also pretty much ignore the possibility of putting just GC together, in any order at all, and HG, in that order.

If one of your letters is an X, what are the odds that a valid word will start with it? Not zero, certainly, but once you’ve eliminated a handful of options, don’t waste your time on it.

Likewise, how much time should you invest in coming up with words that end with Z (if that letter is among your choices for the day)? Again, not very much time.

But then you start to notice how often certain letter combinations are “sticky” — tending to clump together in English words. Maybe HG isn’t likely, but GH? Ye gods, yes: words containing IGH, say, and OUGH. Suffixes like ING practically jump out of the Spelling Bee wheel at you (as in the example shown above), to say nothing of common tense and number suffixes (D/ED and S, respectively).

And then you realize how often English — like German — simply bangs shorter words together into longer ones: get one or the other short word, and maybe you’ll also get the longer. You might have a base group of the letters CIPSTUK, say, which might yield (depending on that central letter!) UPTICK, PICKUP, STICKUP (and of course) TICK, STICK, PICK, TUCK, SUCK, STUCK, and the variations thereof. (See, too, the common combination CK — especially at the end of a syllable.)

It’s hard to break away from the game some days, especially when you realize that your cryptex is full of especially “friendly” letters.

I can’t be the only one stuck in this whirlpool, can I?

I don't subscribe to the NYT games, so while I do play Spelling Bee, I was always get kicked out when I reached the "solid" level. It is interesting to me to see when that is. Depending on the letters, sometimes, I don't have to make many words before the game ending, but on other days, I can make a lot of words.