Book Review: 'The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia,' by Juliet Grames

Death, romance, history, geography, fear -- all tangled up in 1960s Italy

Disclosure: This is a review of a book by a friend of mine. Make of that what you will, but the fact does not bear on the nature of my responses recorded here. I suspect my friend would not have it any other way.

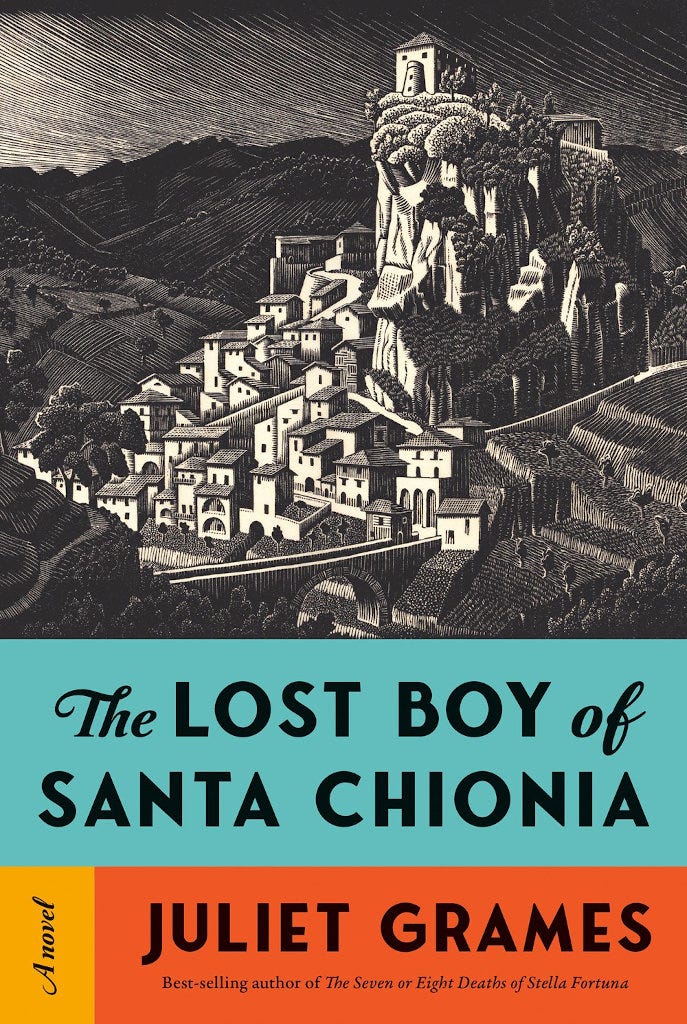

Suppose you’re browsing the fiction shelves of a bookstore, and you overhear someone say, “Santa Chionia.” The operative word clicks on the teeth and rolls around in the speaker’s mouth like an olive pit.

You won’t know the context, but you may find yourself thinking, reflexively: “Ah. Italy, surely.” You listen further — is this book talk, travel talk? — and you hear further hints: “…murder mystery… 20th century… a woman and a man… complicated families… priest… corruption…” At this point you still don’t know if the discussion revolves around fiction or life, but you’ll already be forming further associations, unasked. Something to do with gangsters. Probably exotic food. Overwrought passions. Tragedy and opera…

…and then you see it: the book cover1. Huh, you think: is that Italy? Where’s the… the… awe-inspiring splendor?

Yes, it’s true: this is not the (literally) romantic Italy of pop culture. You might spot an aged, gray, wrinkled Sophia Loren scowling at you from the corner, but there’s no trace of a carefree young Marcello Mastroianni in an expensive linen suit. Tony Soprano would never vacation here, nor would Mario Batali. You might trip over a squat, tawny, long-tongued dog, but you’d never have to dodge a cute little Vespa scooter. Pick a day, any day, and look out the window; it’s probably raining…

The plot, in brief (and as non-spoilery as I can make it):

Francesca Loftfield, an idealistic young American woman from Philadelphia (“a bluestocking with big dreams for building a better world, one needy child at a time”) spends months in 1960-61 in a small town in Calabria. This is the mountainous, southernmost region of Italy — the toe of the boot (extending from the continent as if to kick Sicily aside… or perhaps about to stub itself there). Francesca has arrived in Santa Chionia representing an international charitable organization called Child Rescue. Her task: establishing a nursery school, in a place where the only — brief, limited, private, almost exclusively male — education has only ever been provided by the Catholic Church.

To say that Francesca faces obstacles is to understate the case. There are obvious ones:

Soon after she arrives, a flood tears down the mountainside, demolishing numerous buildings and — critically — washing away a fragile bridge, the only route to or from the outside world.

She must find and equip a building for the school, in a place of ancient structures and forbidding terrain where nothing “new” can likely be built.

That she can speak Italian is of limited value: the town’s history and language have more in common with Greece than with Italy.

Most importantly, she faces the — at best grudging, at worst openly hostile — mindset of a community too often disappointed in its dealings with the “civilized” outside world.

Ironically, the greatest difficulty she must confront is the tentative trust she starts to establish, especially with certain women of Santa Chionia. These women open up to her, especially, to share bitter secrets of their past: old grievances and feuds, tragic deaths and disappearances of family members, mysterious betrayals echoing for generations…

…and exactly because of the town’s cloistered nature, of course, Francesca hears and must acknowledge multiple sides of every poisoned relationship.

It’s a slippery, tortuous route she must navigate. She’ll face threats real as well as imagined. She’ll fall in and out of confused love. She’ll get support from unlikely directions, and lose support from people she’s come to rely on. Skeletons are literally buried and unearthed — some of them, thousands of miles away. And it doesn’t even help that her story is told in the first person: she must survive the experience, obviously, but can she be happy to have lived it?

I’ve tried to thread my own slippery, tortuous route through the above plot summary — not saying too much, nor too little, about what pleasures you’ll encounter in your own reading. But I can talk more freely about the plot’s packaging: the writing.

Grames has got a lot of moving parts to juggle in The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia, and she does so nimbly. It’s the suspense of watching a sleight-of-hand artist toss around an orange, a stiletto, a bottle of expensive Scotch, a sheet of paper, an ice cube, and a whirring power drill: you can’t decide which you prefer — that she drop something, or that she doesn’t.

Her grace notes tend to be brief, revealing of the invisible rather than of the simple physical world: We are tragically too busy, she says, to keep diaries when we are falling in love, and tragically too introspective not to when we are falling out.

But she’s not blind to the sensory, either:

The sun was speeding up in its descent, doing its best to appear a victim of gravity, like us all. I swear I saw the moment it happened—the shift from a yellow ball suspended in the sky to an orange ball sliding into the sea. The drama of the streaks of red lying above the Ionian horizon was exaggerated further by the maroon pall blanketing the backlit mountains. I remember it so perfectly and yet cannot believe my own memory—the extremity of the color was such that it has called into question for me every other memory I’ve carried throughout my life.

One of her tricks which became my favorite to watch, whenever I caught it happening, is the sly trick of slipping into the narrative an occasional, wait, was that a joke I just read?!?:

His hand wrapped around my rib cage, bracing me, and I felt the other slide down my stomach, where it lingered long enough to cause intemperate activity… I had to get him out of my bedroom before I accidentally had sex with him… I was already regretting everything that would not happen.

All the above notwithstanding, a reader may require two particular skills when approaching The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia.

The first requirement: a quick grasp of proper nouns, especially names, especially Italian names… and of the relationships among people known by those names. Within the space of a few pages, you will encounter, for example: Cicca Casile, Emilia Volontà, Donna Adelina Alvaro, Don Tito Lico, Don Pantaleone Bianco, Saverio Legato, Teodoro Iiriti, and many others. You will encounter all these people (and many others) more than once, a few on almost every page; I could eventually carry them all around in my head without mixing them up too much, and suspect that you will do so more quickly. But it was a challenge at first.

Secondly, you may notice, as I did, that Juliet Grames-the-author slips into the narration nominally by Francesca Loftfield-the-protagonist — not at all often, but yes, sometimes. What I’m getting at here is a fondness (which I share) for the English language, its vocabulary in particular — even for potential vocabulary, given the way English words are commonly formed. Here’s a sampling of words whose context didn’t (for me) provide likely meanings; all sent me scurrying to the dictionary, not always successfully:

kwashiorkor

piperazine

murmillo

genialoid (maybe one of the “not a real word yet” examples)

scutch

contusing

I’m not sure I’d classify this as a problem, exactly; some of these words might be very common among people — maybe you? — with special knowledge. (E.g., piperazine is a chemical compound in certain medications which functions to expel parasites from the system; scutching is the act of beating flax or hemp in order to separate out the woody fibers it contains.) I myself wasn’t convinced, though, that Francesca — that naive progressive bluestocking from Main Line Philadelphia — would use them without explanation. And their sudden, one-time appearances did jar me out of my reading rhythm.

Bottom line: The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia will take you to an Italy seldom depicted in guidebooks and splashy pop fiction. It will move you, it will baffle and frighten you, it will teach — or remind — you both of things about history and human nature which you cherish, and of things which you wish you didn’t know. It will reassure you about the power of language in the hands of a writer who knows how to wield it. And it will leave you very, very satisfied.

For what it’s worth, it’s a woodcut, by M.C. Escher, entitled Palizzi, Calabria.