The story so far: Part 1 is here. If you just need a reminder, though: amateur private detectives Guy and Missy Williams are cruising the galaxy aboard a ship called the ISS Tascheter, sometime in the far future. They’re looking into a mystery involving Shawn Dodd, the passenger in the cabin next to theirs. It seems that while entertaining a lady friend, a clone named Yolanda Templeton, Dodd was sucked out into space when a meteor struck a window of his cabin; Yolanda, meanwhile, was secured in Dodd’s airtight bathroom. Over breakfast in the deck’s dining room, Guy has reported the incident to their purser friend, Matty Torricelli… and, since Matty is responsible for both the health of the ship and the safety of passengers in Guy and Missy’s residential wing, he’s quite alarmed.

Guy’s narration continues…:

After that, naturally, there’s no alternative: Matty’s got to see for himself, and I’m not about to stay here. We quickly finish our coffee and head for our residential wing.

On the way, Matty calls up to Incident Control1 to confirm they haven’t received any reports of strikes — reports from the humans aboard or from the ship’s own electronics, quantics, and optics. As for me, I call Missy because I know she’ll be mad if she misses this, and I’ll be mad if I fail to notice or ask about something she herself wouldn’t have overlooked. Matty tells me nothing even close to a meteor strike has been logged for months, for whole dorm-cycles even, and this ship’s never in its history had a roomburst, and I tell him Missy will meet us out in the hall. We can’t bring ourselves to make idle chitchat on the way so we’re silent, lost in our own thoughts.

Matty’s thoughts, I know, probably revolve around practical and technical considerations. He’s weighing points of fact and probability, mechanics and stress and ship’s systems.

Me, I’m just looking around the way I sometimes do, like I’m seeing the ship and its passengers for the first time2:

The crew has decided today will be sunny and warm, so the wall panels are showing us a tropical ocean. The water’s a deep blue, and the complementary sky almost cloudless. Like always, the daytime scenery includes some little touch to remind you you’re not on good old Earth; on this cruise it’s the twin suns, conveniently located in the same part of the sky and together giving off just about the same light as the real thing back “home” does. The air in the hall has been tinkered with until it feels like it should, too — we’re all in short sleeves and tank tops, sundresses and such — and the air moves against our skin like it ought to. If we force ourselves to listen, because naturally you tend to forget the soundtrack when it doesn’t change, we can hear water smacking up against the hull, the deep thrum of what the old oceangoing engines must have sounded and felt like. I guess we’re supposed to be far out in mid-ocean because there aren’t any seabirds squawking at one another or us today. It’s just us and the ship, sailing along in the great wide and picturesque and serene and utterly artificial beauty of the natural world.

Missy meets us at the door to Shawn Dodd’s room. She’s wearing my favorite jumpsuit, the blue sleeveless one which looks like it unzips to here (but I know better — it actually unzips to here, hence my favorite), and around her waist is a sash with a little closed pouch at her waist. On another woman the pouch might contain cosmetics or something of even more mysterious purpose. On Missy, I suspect a flask occupies the pouch. Meanwhile, Durwood is cradled in her arms.3

Missy gives me a look and I know what must have gone through her mind: we both know that (a) when he’s in full-on purser mode Matty can’t stand Pooches, or any other source of potential disorder, and yet (b) Durwood every now and then finds something in a corner or under a dresser that we’d never find on our own.

Sure enough, Matty glares at it. “Keep that thing leashed,” he says. Missy puts it on the floor and presses the button on the back of its neck which will keep it within a couple feet of her via whatever sense they use, even if she loses the remote. Infrared or something. The Pooch wags and looks up at her, then me, then Matty, then at Dodd’s door, and wags again. It doesn’t exactly woof but sort of woofles, impatiently. Translated, I guess, this amounts to: Oh boy. Adventure!

Matty asks Missy about Yolanda. Missy says she must still be unconscious because she didn’t answer her phone4 and didn’t come to the door when Missy knocked. I can see Matty take this information in and consider it, wondering if he should check on the clone first.

But no. Real problems first. Dodd’s room it is.

Matty pulls out his keycard, rechecks Dodd’s room number, hits the button. The room’s unlocked now but first he calls upstairs and asks them to run a pressure check on this section of rooms. Smart guy, I think, and when he gets off the phone I say so. He shakes his head. “Not so much smart, really. Paranoid.” (Po-TAY-to, po-TAH-to, if you ask me.) Out of habit, before opening the door he presses the doorbell button. He looks back at me, grins and rolls his eyes, embarrassed to have forgotten: Oh, right. Nobody home. So much for smarts!

And finally he turns the door handle.

We’ve never been in Dodd’s cabin, Missy and I, so a little bit of curiosity underlies our first glances around the place. The lights are on, which helps. The door to his bathroom’s over on the right instead of the left, and the little zapper range is to the left of the dry sink instead of over it. Otherwise the general orientation is the same. A tiled entry area too small to be dubbed a foyer; living room at the front; bedroom at the back. I assume it’s the bedroom, anyhow — the door’s closed.

But it’s not the general orientation which claims our attention. It’s the specifics.

Chaos everywhere: cabinet and closet doors hanging open, drawers yanked almost out of the walls and dressers, rugs pulled out of true and bunched up. A jumble of trash and clothing, throw pillows and silverware, plates, glasses, and bottles (big surprise) spreads in a big swath across the living room, down the little hallway to the back. Even a couple of pictures still hanging on the walls lean thataway. It’s like somebody picked up the ship and tilted it in that direction, towards the bedroom door, and shook it once or twice before setting it back on the horizontal. It’s obvious right away that Yolanda hasn’t told us the whole truth: everything which is not just lying in the path towards the bedroom door is actually piled up against it. Neither Yolanda nor anyone else has opened that door since whatever-it-was happened.

Durwood’s head is lowered, and The Pooch, apparently worried, does not make any noise at all as it looks from side to side, scanning the unfamiliar rubble — the unfamiliar very fact of rubble in the first place. Then it suddenly comes to alert, noticing what I just noticed myself. Which is: the bathroom door’s open. And inside, nothing out of place. On the vanity’s faux-polished-marble countertop sits a glass with a toothbrush in it. There’s a little rug placed squarely in front of the head. Up closer, we can see a little bottle of aspirin next to the sink. Its lid is off. A couple of aspirin lay on the counter beside it.5

It’s like a bathroom removed from some other cabin — one in a cruise line brochure, maybe — and reinserted into this one, pristine and intact amid the thorough disarray.

And yet, as Matty notes aloud probably for his own benefit as much as ours, it’s also just right. As she said, Yolanda was safely in the airlocked bathroom — probably checking her nails and makeup — at the time the exterior window blew open, the vacuum of space abruptly hoovering everything towards the back until the bedroom door got pulled shut.

By now Durwood is headed for the bathroom. When it reaches the maximum tethering distance from her, I see Missy’s right foot twitch, and I know The Pooch is pulling hard on the virtual leash. We follow along behind it. It goes straight to the back corner under the vanity — the one where the snap-in trash can sits in its track. I think Durwood’s heading to the trash can but no: it’s going for the corner itself. But it can’t get past the can, which is mounted too close to the wall for it to squeeze past.

“Get that thing out of the way,” Matty says.

Missy picks Durwood up and rocks it back and forth a couple of times, patting its head. (It whirs.)

Matty crouches down on all fours and for a crazy moment I imagine he’s about to start barking at the trash can but no, he just grabs the rim around the top and pulls hard. The can snaps out of the track and Matty places it to one side. I’m bending over, looking past his shoulder, and Missy — Pooch in her arms — is likewise bending over and looking past his other shoulder. He picks something up off the floor. He and we stand up.

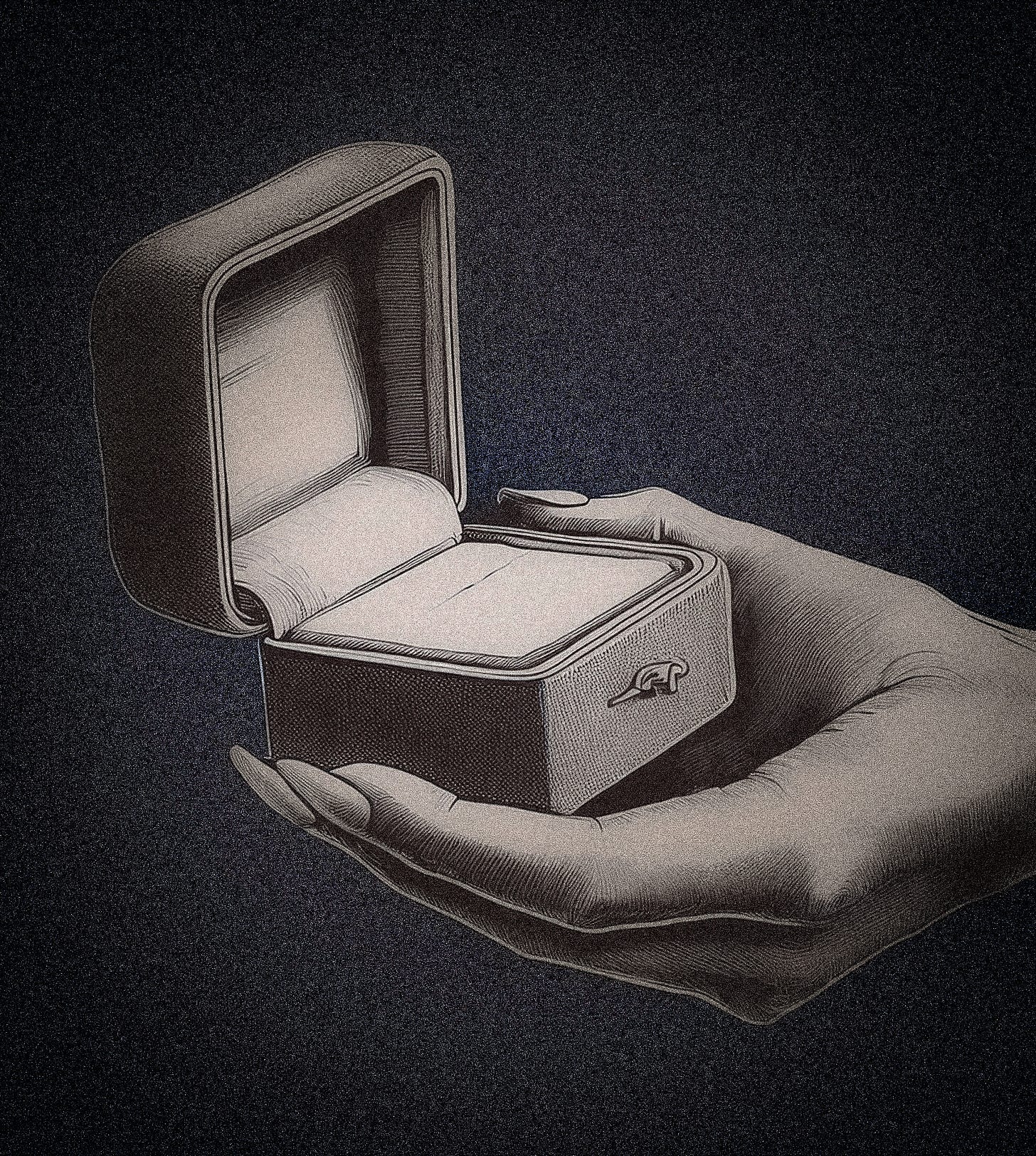

We look down at his hand. On the open palm sits a little maroon velvet-covered box. It is shut.

Of course it doesn’t remain that way for long. Even as she grabs it from Matty’s palm with her free hand, Missy identifies it as a jewelry box — probably for a ring, given that it’s a cube about four or five centimeters on a side. Before she opens it, she turns it over. The underside has a mark burned into it, something that looks like a florid capital “R” except for the way the right foot continues on and over and back again, forming a not-quite-closed circle around the letter.

“That’s the jeweler who made it,” Missy says with something like knowledge before Matty or I can merely guess it. She peers more closely at it, then pauses to think. “I know this one. Wait—”

I interrupt. “Can’t you just open it f—”

“Husband of mine,” she says, which I recognize as my cue to shut up, “shut up. Give me a second.” Another pause.

Matty is starting to radiate impatience and I know he’s eager to open that bedroom door. “Listen, Matty,” I say. “Why don’t you go check the rest of the cabin and Missy and I’ll stay put here. Just do us a favor before you head down the hall, and close the bathroom door behind you. Just, you know—”

He nods. “Just in case.” He goes, and the bathroom door clicks shut. It gives a little sigh like some of the doors on these mature ships do: we’re sealed inside.

The two of us, and probably Durwood, relax a little. In the mystery and excitement I hadn’t noticed how cramped the bathroom was with three humans and a Pooch stuffed inside.

Missy checks her watch. “Still off-ration,” she says. “A little morning tipple, you think?”

She doesn’t even wait for a reply. She unsnaps the pouch’s clasp and, sure enough, withdraws from it a small silver flask. She takes the toothbrush from the glass and puts it aside, and empties the flask into the glass. It’s not an iceglass but she had apparently anticipated this: the orange martini — the breakfast snort — has been pre-chilled, almost to freezing. Not to the slush state, either. It’s perfect and I say so, as I hand the glass back to her. I give her an admiring leer. My wife: she sure can cook.

And then, at last, we return our attention to the ring box.

“The mark,” Missy says. “It’s an R, and it stands for Ri.”

The word comes out sounding like Ree but I know what she’s saying: Ri was two stops ago6, an ancient, cloud-draped world once inhabited by some sort of human-sized creatures, apparently bipedal like us. Its cities, once they’ve been outfitted with the right kind of air-treatment and desalination facilities, provide quite comfortable living accommodations for human tourists and those interested in longer stays.

Among those long-term residents, Missy reminds me: the hundreds of proprietors of an enormous jewelry district down at the equator. At the equator, that is to say, equidistant from the rich Ri-diamond mines at both poles. Ri-diamonds resemble the familiar carbon ones from Earth and a few other planets; on Ri, though, the gems come out of the ground and remain stable at much larger finished sizes than those from elsewhere. And while clear and crystalline, whatever their composition, Ri-diamonds have one unusual refraction property: they alter the wavelength of light passing through them, such that Ri-diamond filters seem to change the natural colors of objects behind them.7

They cost a small fortune. Good ones do, anyhow — and they’re all good ones.

By now Durwood is back on the floor, woofling again as it sniffs around looking for whatever it is that Pooches look for when there’s nothing in sight. Missy sips again at the martini, and over the rim of the glass — she’s taking her time — she is eyeing me, wryly, and she’s hefting the little box in her hand and alternately looking down at it, too. I know what she’s thinking. She’s thinking about the earrings I talked her out of getting during our three-day Ri layover. She puts the glass down on the counter. She raises the box closer to her face, and she at last cocks it open.

From my angle, I can’t see what’s inside. Or rather I should say, I can’t see what’s not inside, but I absolutely know what it is or isn’t, what it might or might not be, because I can see the thwarted-again look in Missy’s eyes. The box is empty.

Not quite empty, though. Yes, the little slot in the little velvet cushion where the — presumed — ring would be stuck, that is empty, and there’s no ring rattling around loose.

But under the lid, fitted snugly in place as though meant to stay there: something is wedged there, all right. A scrap of lightweight folded paper. Missy inserts a well-manicured pinky fingernail under one edge, and picks at the little white square until she can pull it free. Because she can tell I’m feeling left out, and because I pride myself on knowing about things like paper, she hands it — still folded — to me, and picks up the glass, and drains what’s left of the martini.

Carefully, I place the paper on the vanity counter. No smart fibers in this thing. Real cotton paper, as far as I can tell. Lightweight and thin. I open it, one fold at a time.

We read what’s printed there, and we look back and forth at each other, the same questions in our eyes. Then I bend and pick up Durwood — it wriggles, wanting to be transferred to Missy because it’s still leashed to her — and Missy calls out to Matty.

“You still out there, Matty? Okay to open the door?”

I look down at the scrap of paper. It’s a receipt for, yes, a Ri-diamond ring of eight carats. And yes, it cost the purchaser a staggering number of smaller gems in barter. Just as Matty opens the door behind me, I look again at the mystery: the date of purchase.

Ooooohhh... What’s a mystery without another mystery piled on top of it? Find out about the mysterious purchase date (and Shawn Dodd’s fate) in the third and final — and longest — part of “Open and Shut”!

Well, I dunno. “Incident Control” at least sounds kinda like official bureaucratic titlese. But when you think about it, “incidents” tend to be… uh… sort of uncontrolled, don’t they? But such are the perils of writing a story (as I did “Open and Shut”) just to get some words on paper!

This sentence makes me laugh now because, well, at the time I wrote it I really had not looked around much at the ship and its passengers: I was writing each sentence as it came to me, without much thought of where the next one would take me. Remember: “Open and Shut” was pretty much just a writing exercise for me — a way to get myself writing fiction again.

Durwood (introduced in Part 1) is Guy and Missy’s “Pooch,” a small canine-like electromechanical creature sharing the voyage with them.

“Phone”? Eh? What’s a “phone” in a twenty-Nth-century context? Oh, wait — you mean a v-com?

Aspirin tablets: another poorly thought-out anachronism!

“Two stops ago”: in 23kpc, the ship almost never stops at a planet — let alone even comes close enough to make a “stop.” I’d thought more about the practical difficulties of parking a mile-wide asteroid, moving at near-light-speed: how long it would take to slow down, the effects on the passengers and crew of gradually losing their artificial gravity, and so on. But here in “Open and Shut,” I wasn’t even trying to work all that out.

Does all this make sense? Beats me!